Lost in the Backstreets of Galle: Where Sri Lanka Finally Felt Real

You know that feeling when a place stops being just a dot on your travel map and starts breathing? Galle’s old walls kept the crowds, but I slipped behind them—into spice-scented alleys, hidden courtyards, and a fishing village rhythm no guidebook prepared me for. This isn’t about fort selfies or overhyped cafés. It’s about chasing rooster crows at dawn, sharing sweet tea with a potter, and finding magic where maps end. Trust me, the real Sri Lanka whispers—quiet, warm, and wildly alive. In a world where destinations often feel curated for cameras, Galle’s backstreets offer something increasingly rare: authenticity. This is not the polished face of tourism, but the gentle pulse of daily life, where tradition and community shape every corner. For travelers seeking depth over display, this journey beyond the fort walls reveals a Sri Lanka that doesn’t perform—it simply is.

Beyond the Fort: Rethinking Galle’s True Identity

Galle Fort, with its cobbled streets and colonial architecture, is undeniably beautiful. Recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, it draws visitors with its well-preserved ramparts, boutique hotels, and charming cafes. Yet, for all its visual appeal, the fort can feel like a carefully staged exhibit—beautiful, but at times distant from the island’s living culture. The real heartbeat of Galle lies just beyond its stone walls, in neighborhoods where life unfolds without an audience. Here, the air carries the scent of clove and damp earth, not just coffee and sunscreen. The sound of temple bells blends with the rhythmic slap of fishing nets against wooden docks. These are not performances for tourists; they are the unscripted moments of a coastal town that has thrived for centuries.

Stepping outside the fort means shifting from observation to participation. It means walking past laundry strung between homes, hearing children laugh in Sinhala from open windows, and seeing elders sip tea on low wooden stools. The architecture changes, too—modest homes with tiled roofs, family-run shops with hand-painted signs, and small temples tucked into quiet corners. This is not decay or neglect, but continuity. These neighborhoods are not preserved for history’s sake; they are lived in, cared for, and constantly renewed by the people who call them home. The contrast is not about beauty versus ugliness, but about performance versus presence. The fort shows you what Galle once was; the backstreets show you what it still is.

For travelers, this shift in perspective can be transformative. Instead of collecting photos, you begin to collect moments—brief exchanges, sensory impressions, fleeting connections. A woman smiles as she arranges marigolds at a roadside shrine. A fisherman nods as he carries a basket of silver pomfret. These are not staged interactions, but genuine glimpses into a way of life that has changed slowly, if at all. To experience this side of Galle is to move beyond the idea of travel as consumption and toward travel as connection. It requires no special skills, only openness and respect. And in return, it offers something far more valuable than a perfect Instagram shot: a sense of belonging, however brief, to a place that feels deeply, unmistakably real.

Dawn Walks in Pitawala: A Village Waking Up

If there is a moment when Galle feels most alive, it is in the quiet hours before sunrise. Pitawala, a residential neighborhood just north of the fort, comes to life with a rhythm that is both gentle and purposeful. At 5:30 a.m., the sky is still dark, but the streets are already stirring. Fishermen walk toward the jetty, their rubber boots making soft thuds on the wet pavement. Women in saris carry baskets of vegetables from early morning markets. Children pedal bicycles to school, their laughter echoing under the glow of fading streetlights. There are no tour groups, no souvenir hawkers—only the unhurried pulse of daily life.

The jetty at Pitawala is not a tourist attraction. It is a working harbor, where small wooden boats return with the night’s catch. Standing at the edge, you can watch men in rolled-up trousers mend nets with practiced hands, their fingers moving quickly through the tangled threads. The air smells of salt, fish, and damp rope. Seagulls circle overhead, waiting for scraps. Nearby, a few boys jump into the water, their shouts bouncing off the stone walls. This is not a scene staged for visitors; it unfolds the same way every morning, rain or shine, tourist or no tourist.

Walking through Pitawala at this hour is an exercise in mindfulness. The light is soft, golden at first, then pale blue as the sun rises. Palm trees sway in the breeze. A temple bell rings in the distance. Dogs nap in doorways. The pace is slow, almost meditative. This is the kind of stillness that cannot be manufactured—it must be discovered. For travelers accustomed to packed itineraries and crowded landmarks, this quiet immersion can be profoundly grounding. It reminds you that travel is not just about seeing new places, but about experiencing different ways of being.

To make the most of this experience, timing is essential. Arrive between 5:30 and 7:00 a.m., when the village is awake but not yet busy. Enter from the northern gate of the fort, follow the road past the small mosque, and turn left at the junction with the fruit vendor. Wear comfortable shoes and carry a light jacket—the morning air can be cool. Photography should be done with care; always ask permission before taking pictures of people. A smile and a nod go a long way. This is not about capturing the perfect shot, but about honoring the moment as it is. When done with respect, these early walks become more than just sightseeing—they become small acts of presence, quiet acknowledgments of a life that continues, beautifully, beyond the reach of guidebooks.

Hidden Workshops: Meeting Artisans Behind the Scenes

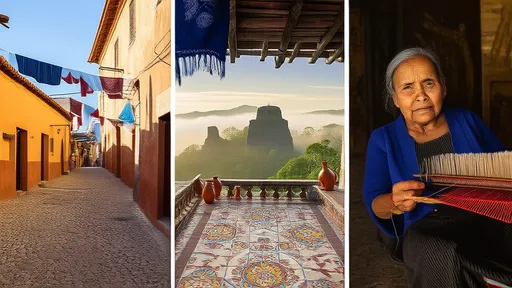

Just a few minutes from the fort’s souvenir shops, where mass-produced trinkets line the shelves, another kind of craft thrives—one rooted in tradition, patience, and pride. In narrow lanes and modest homes, artisans keep ancient skills alive. These are not display pieces for tourists, but working studios where pottery is shaped by hand, lacquer is wound thread by thread, and cloth is woven on wooden looms. These crafts have been passed down through generations, not as hobbies, but as livelihoods and legacies.

One such workshop belongs to a potter in a quiet alley off Hospital Street. His hands, rough and stained with clay, move with quiet confidence as he shapes a small bowl on a foot-powered wheel. The clay comes from a riverbank outside the city; the glaze is made from local minerals. Each piece takes hours to complete, and drying can take days. There is no rush, no factory line—just the steady rhythm of creation. He does not speak much English, but his eyes light up when he shows a finished piece, turning it slowly in the light. This is not just a product; it is a story, shaped by soil, skill, and time.

Nearby, a lacquer worker demonstrates the intricate art of hand-turning. Thin strips of colored thread are wound around wooden bowls and combs, creating vibrant patterns that can’t be replicated by machines. The process is slow, almost meditative. Each item takes hours, sometimes days, to complete. The colors come from natural dyes—turmeric for yellow, indigo for blue. These are not decorations; they are expressions of identity, each pattern carrying meaning known to those who make and use them.

Finding these workshops requires more than a map. They are rarely marked, and few appear in guidebooks. The best way to discover them is through word of mouth—asking a local guide, a shopkeeper, or even a tea vendor. Some community-led walking tours include visits to these artisans, ensuring that interactions are respectful and mutually beneficial. When you do find one, approach with curiosity, not entitlement. Ask questions, but do not demand demonstrations. Buy if you wish, but understand that your purchase is more than a souvenir—it is support for a tradition that might otherwise fade. These artisans do not seek fame or fortune; they seek continuity. By visiting their workshops, you become part of that story—not as a spectator, but as a witness.

The Secret Temple Garden: Serenity Off the Tourist Trail

Just fifteen minutes from the bustle of Galle Fort, nestled in a quiet valley surrounded by jungle, lies a Buddhist temple that few tourists ever see. It has no official name in travel guides, no entrance fee, no souvenir stalls. This is not by accident, but by choice. The monks who live here value stillness, and the community protects its peace. Visitors are welcome, but only those who come with quiet hearts.

The path to the temple winds through coconut groves and jackfruit trees. Birdsong fills the air—kingfishers, mynas, and the occasional peacock call. As you approach, the scent of sandalwood and frangipani grows stronger. The temple sits beside a lotus pond, its pink and white flowers floating like open palms on the water. Stone steps lead to a shaded courtyard where monks sit in meditation, their saffron robes glowing in the morning light. At sunrise, the air fills with chanting—a low, resonant hum that seems to rise from the earth itself.

This is not a performance. The chanting is part of the monks’ daily practice, not a show for visitors. If you sit quietly, you may be invited to join, or simply to observe. There are no rules, only suggestions: remove your shoes before stepping onto the stone platforms, dress modestly, speak in whispers. A small offering—flowers, fruit, or a lit candle—is welcome but never required. What matters most is intention. Come not to check a box, but to listen, to breathe, to be still.

The temple’s simplicity is its power. There are no grand statues, no elaborate rituals—just the quiet dignity of practice. Visitors sit on wooden benches or on the cool stone floor, feeling the morning dew on their feet. Some close their eyes and meditate; others simply watch the light move across the lotus pond. Time slows. Thoughts settle. In a world of constant noise, this place offers something rare: silence that is not empty, but full. Afterward, a short walk leads to a family-run teashop, where you can warm your hands around a clay cup of sweet, spiced tea and eat a steamed rice cake wrapped in banana leaf. It is a perfect ending—simple, nourishing, and deeply human.

Coastal Trails to Unnamed Coves

While beaches like Unawatuna and Mirissa draw crowds with their golden sands and beachfront bars, Galle’s coastline holds quieter treasures—small, unnamed coves accessible only by foot. These are not hidden in the sense of being secret, but in the sense of being overlooked. They do not appear on most maps, have no chairs for rent, no music, no vendors. They are used by local fishermen and families, not tourists. To reach them is to trade convenience for discovery.

One such trail begins at Dalawella, just south of the fort. From the main road, a narrow footpath follows the cliff edge, winding past rock pools, sea grapes, and wild hibiscus. The path is uneven, sometimes slippery after rain, so sturdy footwear is essential. As you walk, the sound of traffic fades, replaced by the crash of waves and the cry of gulls. After about twenty minutes, the trail descends to a small bay—a crescent of white sand framed by black rocks. The water is clear, turquoise near the shore, deepening to sapphire further out. At low tide, you can wade to a small island connected by a sandbar.

This is not a beach for lounging, but for exploring. Children jump from low cliffs into deep pools. Fishermen mend nets under palm trees. Sometimes, you’ll see a family cooking a simple meal over a fire. There are no facilities, no shade structures—just nature in its unfiltered state. The experience is not about comfort, but about connection. Floating in the warm water, you feel the current, the sun, the salt on your skin. You are not separate from the place; you are part of it.

Safety is important. Always check the tide before entering the water—some coves become cut off at high tide. Avoid swimming alone, and never jump into water you haven’t seen. Stick to marked paths where they exist, and avoid disturbing wildlife. Leave no trace: carry out everything you bring in. These coves are not public parks; they are shared spaces, respected by those who know them. By traveling lightly and mindfully, you honor that respect. And in return, you are rewarded with something few places offer anymore: solitude, beauty, and the quiet thrill of having found something real.

Eating Like a Local: Beyond Café Culture

Galle’s food scene is often reduced to its Instagram-famous cafes—places with floral walls, avocado toast, and cold brew. While these have their place, they represent only a fraction of what the region offers. The true flavors of Galle are found in modest, unassuming places: open-air counters where women serve rice and curry from steel pots, roadside stalls where kottu is chopped on a hot griddle, and family kitchens that open at dawn to serve hoppers with spicy sambol.

Rice and curry, the staple of Sri Lankan meals, is best eaten at a local “hot eat” counter. These are not restaurants in the Western sense, but small, open-air spaces where meals are served on banana leaves or metal plates. The curry selection changes daily—sometimes jackfruit curry, sometimes dhal with coconut milk, sometimes bitter gourd with mustard seeds. The rice is always steamed, fragrant with pandan leaf. A meal costs little, but the flavor is rich, layered, and deeply satisfying. Hygiene varies, so look for busy spots with high turnover—fresh food, clean hands, covered containers.

Kottu, a beloved street food, is made by chopping roti, vegetables, egg, and sometimes meat on a hot iron plate. The rhythmic clanging of the metal spatulas is a familiar sound in the evenings. The result is a spicy, savory mix that warms you from the inside. Best eaten standing up, with a cold king coconut on the side. Hoppers—bowl-shaped fermented rice pancakes—are a morning favorite, often served with a soft-boiled egg in the center and a side of coconut sambol. They are light, slightly sour, and perfect with a cup of strong, sweet tea.

To eat like a local, you must let go of expectations. There may be no menu, no chairs, no English spoken. Order by pointing, smiling, or repeating the name of the dish. Eat with your right hand, as most locals do, and don’t be afraid to get messy. This is not about fine dining; it’s about real food, made with care, shared with pride. And in that sharing, you taste not just the meal, but the culture—the warmth, the generosity, the quiet dignity of a people who feed others as an act of love.

How to Travel This Way: Practical Ethics and Logistics

Traveling beyond the tourist trail is not about rejecting comfort, but about choosing connection. It requires a shift in mindset—from seeing travel as a series of destinations to experiencing it as a series of relationships. The good news is that it doesn’t require special skills, only intention. Start by hiring a local walking guide. Many are former fishermen or teachers who know the backstreets intimately. They can lead you to hidden workshops, introduce you to artisans, and explain cultural norms in real time. Their knowledge is invaluable, and your support helps sustain their communities.

Use tuk-tuks for short hops between neighborhoods, but negotiate the fare politely before starting. Avoid over-negotiating—fair pay is part of respectful travel. When visiting villages or temples, dress modestly: cover shoulders and knees, remove shoes when required. Ask permission before taking photos of people, especially children and elders. A smile and a gesture go further than words. Carry a reusable water bottle, avoid single-use plastics, and dispose of waste properly. These small acts of care show that you are not just passing through, but paying attention.

Slow down. Eat at local spots. Sit and watch. Listen more than you speak. These are not passive acts, but forms of respect. Offbeat travel is not about escaping people, but about connecting more deeply—with places, with cultures, with yourself. It is not always easy; it can be uncomfortable, uncertain, even humbling. But it is always honest. And in that honesty, you find something rare: a version of travel that leaves you changed, not just with photos, but with memories that feel like they belong to you, not just your feed.

In the end, Galle’s backstreets taught me that the real magic of travel is not in the places we see, but in the moments we allow ourselves to be seen. It is in the shared silence with a potter, the nod from a fisherman, the taste of tea offered without expectation. These are not experiences you can plan or purchase. They happen when you stop performing and start being present. And when you do, you realize something simple but profound: the world is not a stage. It is a home. And sometimes, if you walk quietly enough, you are welcomed in.