You Won't Believe This Underground Food Scene in Kinshasa

Kinshasa isn’t just Africa’s third-largest city—it’s a flavor bomb waiting to explode on your taste buds. I went looking for dinner and found something way deeper: secret backyard kitchens, midnight spice markets, and meals cooked with stories, not recipes. This isn’t tourist menu stuff. This is real—smoky, loud, and alive. If you think you know Congolese food, think again. The true magic? It’s hidden in plain sight, served with a smile and a side of rhythm.

The Heartbeat of Kinshasa: Where Food Meets Culture

In Kinshasa, food is never just about nourishment. It’s the pulse of community life, the rhythm that ties neighbors together, and a language spoken through shared platters and simmering pots. More than ten million people call this sprawling city home, and every day, its streets come alive with the sounds of sizzling grills, clattering pots, and the laughter of families gathered around simple tables under open skies. Dining here is not a private act—it’s a public celebration of identity, resilience, and warmth. Meals unfold in courtyards, on sidewalks, and beneath the glow of kerosene lamps, where strangers become companions over a plate of fufu and stew.

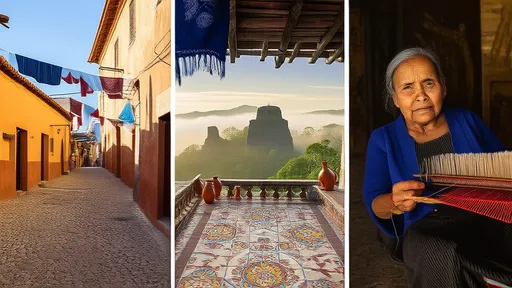

The city’s energy is contagious, and food is at the center of it all. Street vendors balance towering baskets of plantains on their heads, calling out prices with practiced ease. Women in brightly colored wrappers stir giant cauldrons of peanut-based sauces, while men tend charcoal grills sending plumes of fragrant smoke into the evening air. These scenes are not staged for cameras; they are the everyday reality of a city that feeds itself with creativity and pride. Unlike the sanitized dining experiences found in global chain restaurants, Kinshasa’s food culture thrives on authenticity, spontaneity, and deep-rooted tradition.

Yet, this vibrant culinary world remains largely invisible to most visitors. Guidebooks often overlook it, and mainstream tourism rarely ventures beyond hotel buffets or expat-friendly cafes. The real stories—of grandmothers passing down recipes, of young cooks reviving ancestral techniques, of communities bonding over slow-cooked meals—are rarely captured in glossy travel brochures. To experience them, you must step off the beaten path, listen closely, and let local rhythms guide your journey. The heart of Kinshasa beats strongest where the food is homemade, the laughter is unscripted, and the welcome is genuine.

Beyond the Menu: Discovering Hidden Kitchens

One of the most authentic ways to taste Kinshasa’s soul is through its maquis—modest, open-air eateries tucked into residential neighborhoods, often marked only by a hand-painted sign or a cluster of plastic chairs under a tarp. These are not restaurants in the Western sense. They are family-run spaces where home cooking meets communal dining, and where the menu changes daily based on what’s fresh and available. There’s no online reservation system, no Instagrammable decor—just the promise of hearty food, warm company, and a real connection to place.

I first encountered a maquis by chance, drawn in by the scent of grilled meat and the sound of Congolese rumba drifting from a quiet alleyway as the sun dipped below the skyline. What looked like an ordinary courtyard had transformed into a bustling dining hall. Men in crisp button-downs sat beside motorcycle taxi drivers, all sharing plates of golden-brown brochettes and steaming mounds of fufu. A woman in a floral headwrap moved between tables, refilling bowls of rich, dark pondu—a cassava leaf stew slow-cooked with onions, garlic, and a hint of chili. The air was thick with smoke, music, and the easy camaraderie of people who had come not just to eat, but to belong.

The dishes served in these hidden kitchens are the backbone of Congolese cuisine. Saka-saka, made from pounded cassava leaves and often enriched with peanut butter or palm oil, carries a deep, earthy flavor that lingers on the palate. Pondu is similarly beloved, its bitterness balanced by slow cooking and seasoned with smoked fish or dried meat. Goat brochettes, marinated in a blend of garlic, lemon, and local spices, are grilled over open flames until charred at the edges and tender within. Served with a side of boiled plantains or a mound of fufu—a smooth, dough-like staple made from cassava or yams—each bite tells a story of resourcefulness, flavor, and care.

The Secret Spots Only Locals Know

Beyond the maquis, Kinshasa’s most memorable meals often happen in places that don’t appear on any map. These are the home-based kitchens, unmarked market stalls, and Sunday pop-ups that thrive on word-of-mouth and trust. In a city where formal infrastructure can be unreliable, these informal food spaces are a testament to ingenuity and community spirit. They are not designed for tourists, but for locals who know exactly where to go when hunger strikes or celebration calls.

One such experience took me to a quiet neighborhood on the outskirts of Gombe, where a middle-aged woman named Madame Nzola opens her courtyard every Saturday evening to neighbors and invited guests. There’s no sign, no menu, and no fixed price. You arrive, you greet the host, and you take a seat among friends old and new. That night, she served moambe chicken—a dish made with palm nut sauce, simmered for hours until the meat fell off the bone, its deep red hue glistening under the string lights. Alongside it were fried plantains, a mound of fufu, and a fresh salad of tomatoes and onions dressed with lime.

What made the evening unforgettable wasn’t just the food, but the atmosphere. Children played in the corner, elders shared stories in Lingala, and a young guitarist strummed melodies that everyone seemed to know by heart. There was no rush, no pressure to leave. Time moved differently here—slower, more intentional. Access to spaces like this depends on relationships. You can’t simply show up; you need an introduction, a local friend, or a guide who understands the unspoken rules. It’s not about exclusivity, but respect. These are private homes, not performance venues, and the people who open them do so out of generosity, not obligation.

Taste of the Real: What Makes Congolese Cuisine Unique

Congolese cuisine is built on simplicity, patience, and a deep connection to the land. Its foundation lies in a few core ingredients: cassava, plantains, peanuts, leafy greens, and palm oil. These are not exotic novelties—they are daily staples, transformed through time-honored techniques into dishes of remarkable depth and comfort. Unlike the fast-paced, fusion-driven trends of global food culture, Congolese cooking values slow transformation. Stews simmer for hours. Meats are grilled over smoldering coals. Sauces are stirred by hand, their flavors deepening with every turn of the spoon.

One of the most distinctive elements is moambe sauce, made from the pulp of red palm nuts. Rich, slightly sweet, and deeply savory, it forms the base of many traditional dishes, including the national favorite, moambe chicken. The sauce is labor-intensive to prepare, requiring the nuts to be boiled, pounded, and strained to extract the oil and pulp. Yet, the result is worth the effort—a velvety, aromatic stew that coats the tongue and warms the soul. Another hallmark is the use of smoked fish and dried meats, which add umami depth to otherwise simple vegetable dishes, especially in regions where fresh protein is less accessible.

Grilling, too, plays a central role. Street vendors and home cooks alike rely on charcoal grills to cook everything from skewered meats to whole fish. The smoke infuses the food with a distinct flavor that cannot be replicated in a kitchen oven. This method is not just about taste—it’s about tradition. The act of tending the fire, watching the flames, and turning the skewers is a ritual passed down through generations. When you eat grilled brochettes in Kinshasa, you’re not just tasting meat and spice; you’re tasting history, resilience, and the everyday artistry of survival.

How to Find These Experiences Responsibly

For travelers eager to explore Kinshasa’s underground food scene, the key is not just curiosity, but respect. These spaces are not attractions—they are living parts of the community, where people gather to eat, connect, and sustain their way of life. To enter them with humility is to honor their purpose. The best way to begin is with a local guide—someone who knows the neighborhoods, speaks the language, and understands the cultural nuances. Food-focused walking tours, offered by small local enterprises, can provide safe, ethical access to hidden kitchens while ensuring that income stays within the community.

Another option is to connect through cultural centers or community organizations that host dining events or cooking workshops. These gatherings often welcome visitors and offer a structured yet authentic way to experience Congolese cuisine. Learning a few basic phrases in Lingala—such as mbote (hello), nakipaka te (thank you), or mbala mpo mbala (delicious)—goes a long way in building rapport and showing appreciation. A simple greeting, a smile, and a willingness to follow local customs can open doors that no guidebook can.

Tipping fairly is another important practice. In many of these informal settings, there is no fixed price, and payment is often based on what guests feel the meal was worth. Offering a modest but respectful amount acknowledges the time, effort, and hospitality involved. Above all, visitors should avoid treating these spaces as spectacles. Taking photos should be done with permission, and conversations should be grounded in genuine interest, not voyeurism. These are homes, not stages. The goal is not to collect experiences like trophies, but to share in a moment of human connection.

The Rhythm of the Meal: More Than Just Eating

A meal in Kinshasa is rarely a quick affair. It is an event, a gathering, a slow unfolding of time and conversation. Evenings stretch on, fueled by music, stories, and the constant arrival of new guests. I remember one night in a courtyard in Matonge, where a simple dinner turned into a hours-long celebration. A guitarist began to play, his fingers dancing over the strings, and soon others joined in—singing, clapping, swaying in their seats. Platters were passed and refilled, glasses of ginger juice and homemade palm wine circulated, and laughter rose above the hum of the city.

Children sat at a separate table, giggling over sweet fried plantains, while elders shared tales of Kinshasa in the 1970s—of music, markets, and the changing face of the city. The food was delicious, yes, but it was the atmosphere that left the deepest impression. There was no rush to finish, no glancing at watches. The meal set its own pace, and everyone adjusted to it. This rhythm—leisurely, communal, deeply human—is central to Kinshasa’s spirit. By day, the city is chaotic: traffic jams, noise, the scramble of daily life. But by night, in these intimate gatherings, a different energy emerges—one of warmth, connection, and quiet joy.

Music is almost always present, whether it’s a full band or a single instrument. Congolese rumba, soukous, and ndombolo are not just genres—they are the soundtrack of life, woven into every celebration, every gathering, every shared meal. The beat mirrors the rhythm of the cooking itself: steady, layered, full of improvisation. To eat in Kinshasa is to be drawn into this flow, to let go of time, and to become part of something larger than oneself.

Why This Matters: Preserving Authentic Food Cultures

As Kinshasa continues to grow and modernize, its underground food culture faces increasing pressure. Gentrification, rising rents, and the push for formalized businesses threaten the survival of maquis and home kitchens. Some popular spots have already been displaced to make way for new developments, while others risk losing their authenticity as they adapt to tourist demand. There is a delicate balance between sharing these traditions with the world and preserving their integrity. When done poorly, tourism can turn living cultures into performances, stripping them of meaning and reducing them to commodities.

But when done with care, travel can be a force for good. Sustainable tourism—rooted in respect, reciprocity, and long-term relationships—can support local economies, empower women who run home kitchens, and help preserve culinary knowledge that might otherwise fade. By choosing to eat in community spaces, pay fairly, and listen deeply, travelers contribute to a model of tourism that honors, rather than exploits, the places they visit. Every plate of saka-saka, every shared smile over a pot of moambe, becomes an act of cultural preservation.

The underground food scene of Kinshasa is more than a collection of meals—it is a living archive of resilience, creativity, and human connection. It reminds us that the most meaningful travel experiences are not found in five-star restaurants or curated tours, but in the quiet courtyards, the smoky alleyways, and the open hearts of people who welcome you not as a customer, but as a guest. To taste this city is to understand it. And to understand it is to leave changed—not just by what you’ve eaten, but by what you’ve felt. So seek flavor with humility. Listen before you speak. Eat with gratitude. And let Kinshasa feed not just your body, but your soul.